amity

Images and text from ‘Amity’, a collaboration and exhibition of textile art and installation by Emily Murch (Melbourne) and Ruth Halbert, shown at Vancouver Arts Centre, Albany, WA, in November 2018.

amity

Ruth Halbert & Emily Murch

November 2018

The exhibition amity was commissioned by the City of Albany as part of its Centenary of Armistice commemorations. It was exhibited at Vancouver Arts Centre, Albany.

Artists’ Statement

Amity is a collaboration between Ruth Halbert from Denmark WA and Emily Murch from Melbourne. Emily and Ruth both use textiles, text and installation in their practices, often looking at current social issues through a historical lens.

The Centenary of Armistice is an opportunity to focus on which voices are remembered and which voices are overlooked and silenced and what they can say about the world today. One hundred years on from the ‘war to end all wars’ how close are we to the goal of amity, to mutual understanding and peaceful relationships? Peace is much more than an absence of war. This exhibition is a challenge to people and their institutions to actively work for peace.

The starting point for amity was The Albany Advertiser’s lively report of the spontaneous celebrations in the town on 8th November 1918 when premature news of a ceasefire arrived. It also included reports of war action. Throughout WW1 these reports described the intense, unrelenting noise of the front. When the ceasefire was called, the silence there was profound. In Albany, when the news of the ceasefire arrived, the everyday noises were interrupted by a cacophony of celebration - bell-ringing, sirens, the brass band and people singing. We have painted panels with the ‘noisy’ patterns of ‘Dazzle’ (the name given to geometric camouflage painted on WW1 ships) and hung them leading into the ‘quiet’ gallery to replicate these shifts between sound and silence.

The voices reported in the newspaper were those of civilian officials. They spoke of hope for peace and gave thanks for the sacrifice of the people who served. However their hope only extended to the Allies and they called for heavy recompense from the defeated nations. Nationally, the Prime Minister, Billie Hughes, negotiated fiercely at the Treaty of Versailles and brought home gains for Australia. These are presented as newspaper posters against the wall. The reparations can be seen to have direct links to current political issues in Australia, a few of which we present alongside the posters with a copy of the 1918 Albany Advertiser.

The 100-year-old newspaper’s narrative was exclusively that of white men in positions of power. Women appeared as minor characters in relation to men. Indigenous voices were completely absent. Textile artworks which reference the body in the form of clothing or comfort can embody the presence of the people whose voices were marginalised. Empty clothing suggests absence, and misshapen socks evoke disfigurement or trauma. There is a circle of hand knitted war socks caught mid-stride on the gallery’s floor. Five, 100-year-old, handmade chemises have been placed, waiting, on chairs.

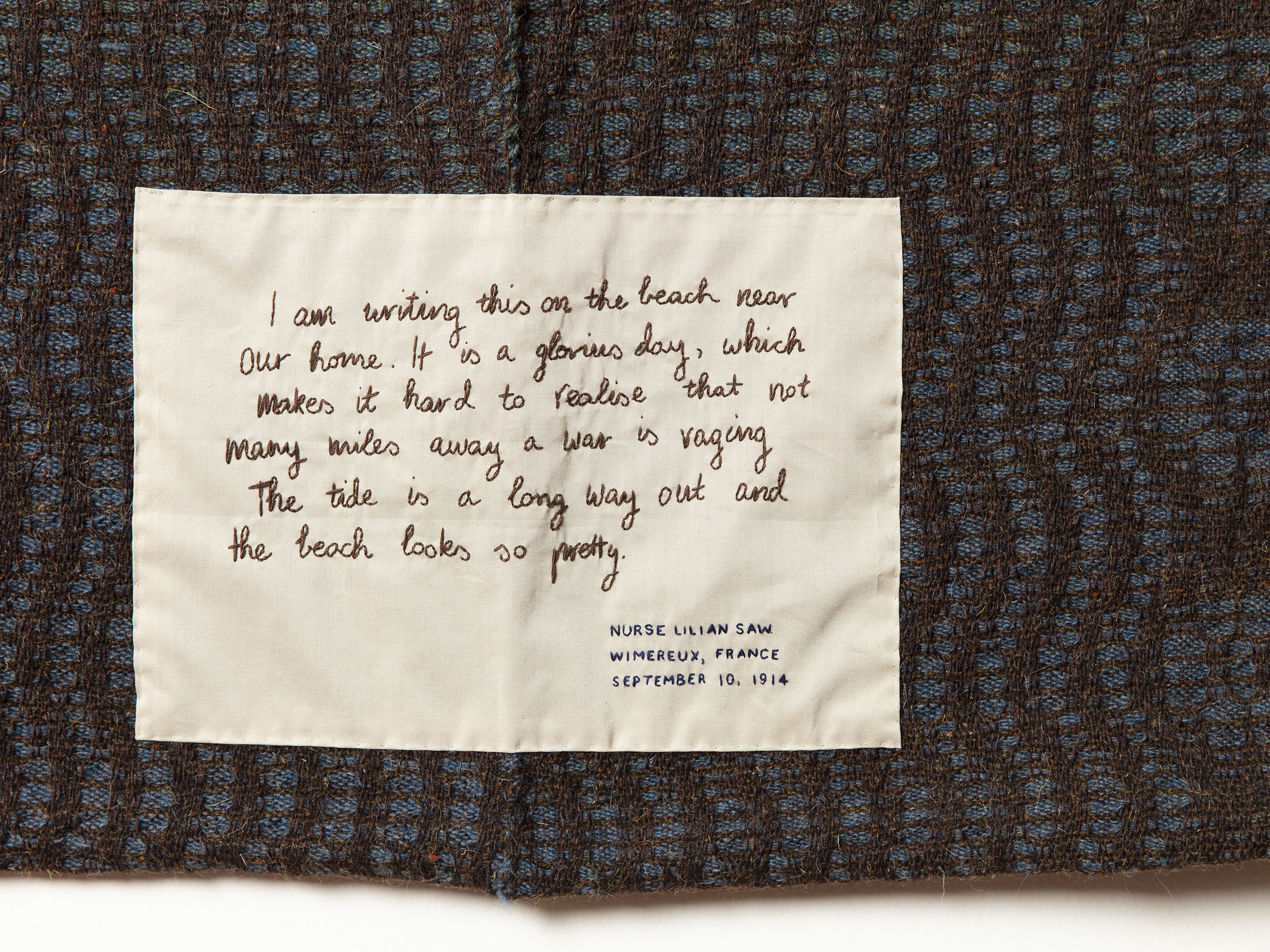

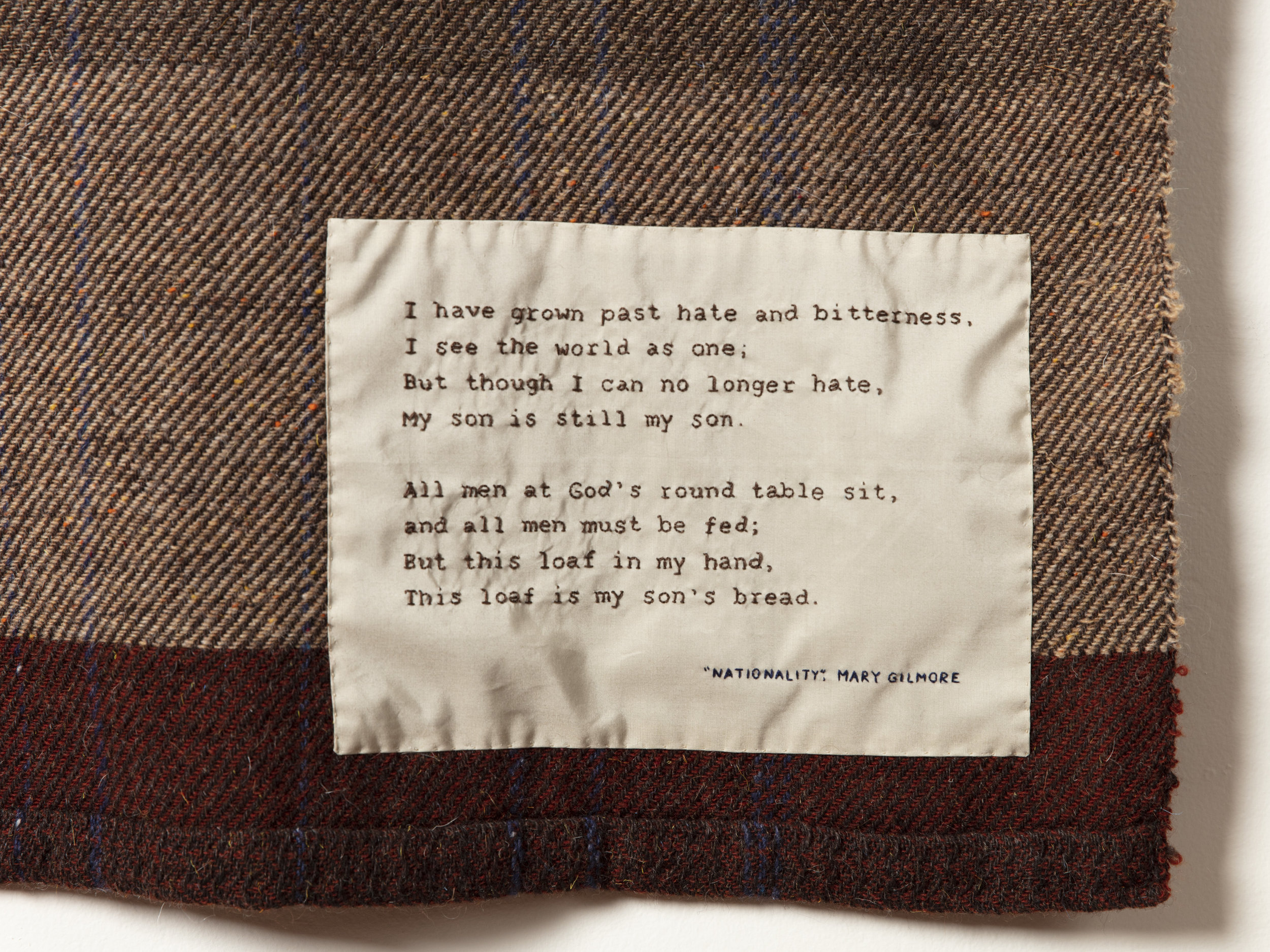

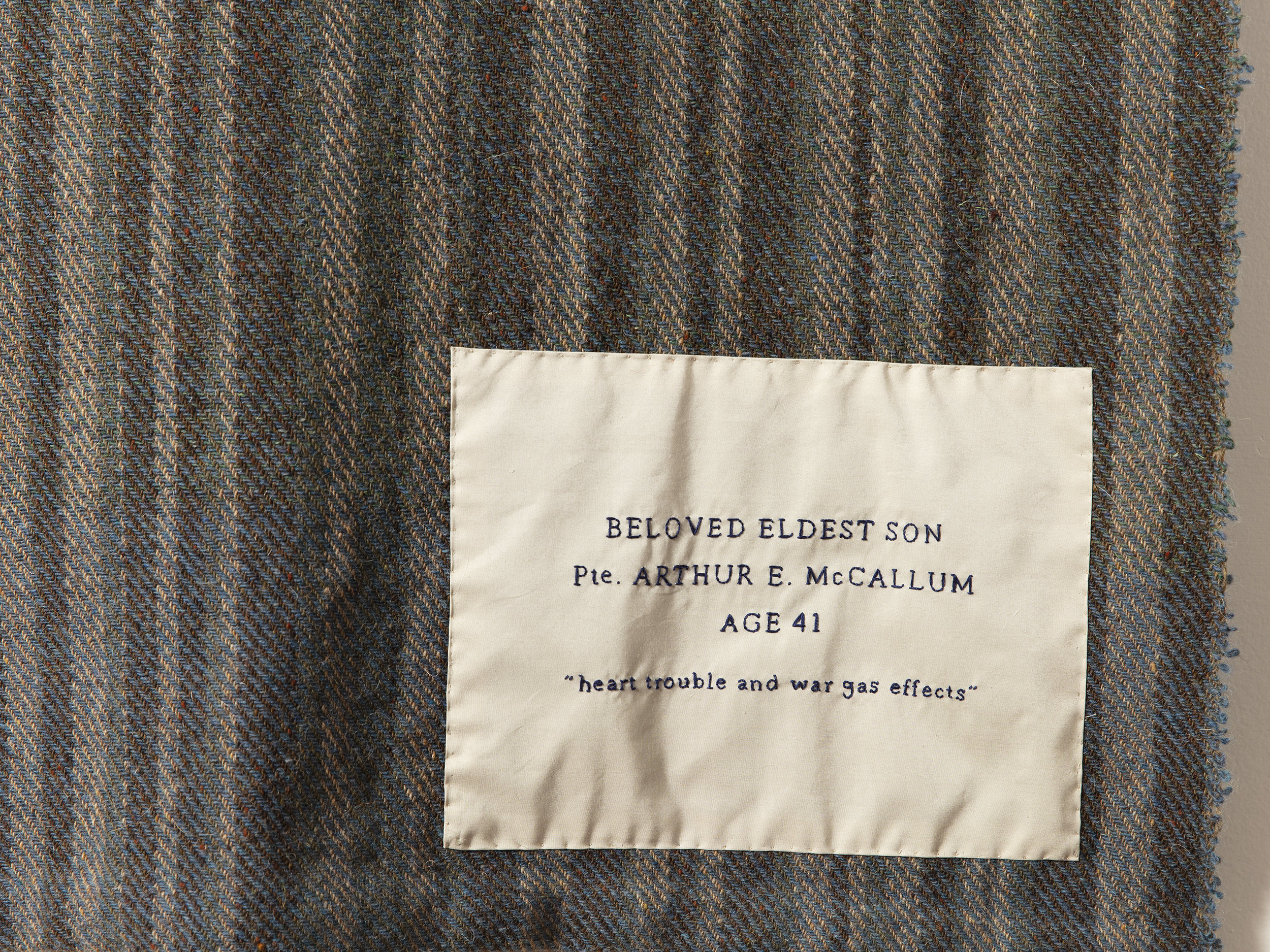

When functional textiles like blankets are hung on the wall there is a tension between recognising them as domestic objects or as part of a soldier’s kit, and as a visual surface to read and to look for meaning. We have hung five handwoven blankets on the wall, each with a hand stitched ‘label’ which carries fragments of under-represented stories.

Blankets and handmade clothing represent the domestic labour of women which has been largely overlooked. They also refer to the handcrafts that women artists taught to convalescing and shell-shocked soldiers after the war. In the spirit of the women’s efforts, the exhibition program includes sock knitting classes and mending sessions that will provide not only an opportunity to develop skills but a forum for discussion among the artists and community on the themes present in the exhibition. Handmade and shared decorations were also part of the Armistice celebrations. The Advertiser reported that bunting ‘appeared from every window’. Making and flying bunting is frivolous act. We will share this sense of hope in drop-in bunting-making sessions in the gallery during the exhibition.

The Vancouver Arts Centre’s history as a hospital is a strong presence and brings echoes of convalescence and quietness to the exhibition. ‘Amity’ does not aim to neatly summarise Armistice history nor to provide a tidy narrative. This exhibition lifts some events and images from the time of Armistice and asks the audience to consider them in light of today.

Opening night statement

Armistice Day, like ANZAC day, has become part of the story we all tell ourselves about who we are as Australians. The effort, struggle, sacrifice, camaraderie and commitment to each other and to justice and freedom are celebrated and memorialised.

We see these admirable qualities in the service and sacrifice of Australia’s servicemen and women, we see Australia as having those qualities, and so we attach ourselves to these qualities. In events such as this Commemoration of Armistice we are encouraged to claim these qualities. If the ANZAC qualities in World War 1 can define Australia, and we are Australian, then we claim we have earned these qualities too.

Qualities such as:

Fairness.

Mateship.

Bravery.

We believe it is a lie.

If we Australians are fair, then why don’t we listen to the First Peoples, the owners of the land who have the oldest continuous culture in the world, and take the Uluru Statement to our hearts, ask for their forgiveness and their guidance for our future together?

If we Australians value mateship, then why do we withhold it and exclude so many people from living fully and freely in this country? Women. Differently abled. Elderly. LGBTQI. Migrants. Refugees. Since when does mateship mean a long list of who we refuse to be mates with?

If we Australians are brave then why have we acquiesced to the lies about refugees? Why have we turned a blind eye deliberately for 5 ½ years to the torture we inflict on a few thousand men, women and children locked away on remote tropical islands in New Guinea and Nauru?

If we Australians dare to aspire to the qualities we revere in the ANZACs then we must continue to be active in fighting for them. For mateship that is inclusive. For fairness for every person on the soil of Australia. And in the daily practice of bravery and justice.

With thanks to:

City of Albany for funding which partly supported the project

Bo Wong, photographer.